This is the first of a two-part series on the history, changing terms and dysfunctionality of the Government Camp-Cooper Spur land exchange. Part II will run in next Wednesday’s edition.

MT. HOOD — Sprawling cities confined by urban growth boundaries. Protection for critical, endemic farmland and open space. Broad rights of public participation in land use decisions. How Oregon has managed its growth since statehood stands as an outlier.

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, Gov. Tom McCall, Sen. Hector Macpherson and many others sought to strike a balance between conservation and development — to encourage compact, efficient growth while preserving Oregon’s character. With the passage of Senate Bill 100 in 1973, they largely succeeded. Robust metropolises border — but don’t overreach into — fertile valleys and forests.

Those successes, however, didn’t come without challenges, and land use conflicts continued. Locally, the United States Forest Service, Mt. Hood Meadows, the board of county commissioners and conservation group Thrive Hood River have spent over two decades in a cycle of failed agreements, muddled bureaucracy and lawsuits over the north side of our famed mountain.

The entire dispute revolves around 770 acres of land at Cooper Spur owned by Meadows. Since opening in 1968, Meadows has made two attempts to construct a destination resort at Cooper Spur, and Thrive, formerly the Hood River Valley Residents Committee (HRVRC), coalesced in part to oppose those bids.

“It’s really about the long-term survival of natural lands in the Hood River Valley for future generations,” said Mike McCarthy, a Thrive Board member and orchardist near Meadow’s property.

But in 2001, Meadows purchased the Inn at Cooper Spur and the Cooper Spur Ski Area, and in 2002, Hood River County exchanged 614 acres of forest it owned near Cooper Spur with 786 acres Meadows held. The newly acquired land made development ever more possible, so the two parties wrangled again.

“We respect Mount Hood, we respect the land and its natural resources, and we really have since day one. We’re all native Oregonians,” said Matthew Drake, the CEO of Meadows, during a presentation to Hood River’s Rotary Club last November. “We also expect to receive fair value for our assets.”

Much has happened since 2002, oftentimes obscure and occurring behind closed doors. This story will walk through part of the Government Camp-Cooper Spur land exchange, including its early history and a promising deal that has since changed, but remains sought after.

The first land swap

Hood River County pursued the original trade to consolidate county-owned forests and gain access to premium timber. Commissioners held the first public hearing on Aug. 6, 2001, and a critical sticking point was the Crystal Spring watershed, which runs directly through Cooper Spur and provides drinking water to about 6,000 county residents.

According to Oregon Revised Statute 275.335, counties may exchange land when “such exchange is for equal value and is in the best interest of the county.” With the county’s land appraised at $1.3 million and Meadows’ holdings valued at $2.3 million, commissioners satisfied the equal value clause by paying just over $1 million to Meadows, making up the difference. But HRVRC claimed the deal wasn’t in the public’s best interest.

“While we are terribly concerned about the potential for development in this area, even more offensive to us and to the taxpayers of Hood River County is the transfer of public funds to pay a private developer for land that has been illegally estimated at a fraction of its fair value,” said McCarthy in a 2002 interview.

Though the county considered land and timber value when appraising the parcels, HRVRC argued they also must account for commercial value. At the time, developable property nearby was selling for $40,000 per quarter acre, but the county slated its own land at $328 per acre.

“The formula for appraisals has to be based on the land’s highest and best use under current zoning, the law doesn’t allow for speculation,” said Will Carey, then county land use attorney, in response to McCarthy. “If you try to go outside that boundary, you’re acting on pure conjecture.”

Given that Meadows had publicly stated plans to build a 450-unit complex, golf course, amphitheater and other amenities at Cooper Spur, it was far from speculative for HRVRC. They also alleged the county failed to give adequate notice of the public hearing. Officials listed the hearing date in two editions of the Hood River News the week prior, but state law requires publication in two different media sources if a two-week notification period was not given.

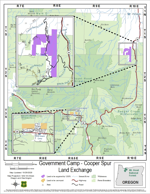

Under the “clean sweep” settlement agreement, Mt. Hood Meadows would exchange 770 acres of property it owns at Cooper Spur (purple) to the United States Forest Service for rights to develop 120 acres in Government Camp (orange).

As such, HRVRC and McCarthy filed an Amended Petition for Writ of Review to Hood River County’s Circuit Court on March 27, 2002, based largely on those arguments. Judge Donald Hull, now retired, dismissed the case in July, but Thrive successfully appealed Hull’s decision in June 2004. Put on hold after separate legislation, federal review and litigation, the case reignited in 2021.

Judge John Olson presided over the trial on Aug. 3, 2023, and issued his verdict a few months later on Nov. 14, rejecting the petitioners’ claims with one exception.

“I cannot discern from the record that the requisite underlying valuation reports were ever presented to the BOC [board of commissioners] for its review,” wrote Olson, clarifying he could only find that a summary of the reports was provided. “I will therefore enter a judgment remanding the case back to the BOC to allow it to review the underlying reports.”

Commissioners then simply had to reexamine the necessary documents and include them in the public record. As previously reported by Columbia Gorge News, commissioners did so and reaffirmed the original trade during an Oct. 21 meeting last year. But that’s just one small piece of the puzzle.

An idealistic compromise: the “clean sweep”

After Hull originally dismissed HRVRC’s case, the committee, McCarthy, the county and Meadows began mediation talks, clearly at a stalemate. As a private and confidential process, Columbia Gorge News does not know what was discussed in mediation, only that it occurred in good faith.

“If you agree to something and you all work on it, it’s a promise,” said McCarthy. “It’s like a sacred promise.”

And they did reach an agreement — the fabled “clean sweep” — in 2005. Under the settlement, Meadows would trade all 770 acres of its land at Cooper Spur for rights to develop 120 acres in Government Camp, effectively preserving the north side of Mount Hood. Another land exchange to resolve the original one.

Congress codified those terms in the Omnibus Public Lands Act of 2009, mandating the trade to occur no later than 16 months after the bill was passed. Upon completion, the exchange would also create the Crystal Springs Watershed Resource Management Unit, setting aside 2,700 acres as a protected riparian zone, and incorporate 1,710 more acres into the Mt. Hood Wilderness. Enter the United States Forest Service (USFS).

USFS owns the Government Camp land and is the agency responsible for carrying the trade out, but by 2015, nothing had been finalized. USFS was reportedly busy adjusting boundary lines, resolving title issues, configuring right-of-way easements and more during that time.

“I think the delay was caused by several things. Part of it was just turnover in staff,” said Heather Staten, the former executive director of HRVRC, now Thrive. “The Forest Service is also very process-oriented — there’s like 60 steps to a land trade.”

As a result, Thrive filed suit against USFS for “unreasonable delay” in the U.S. District Court of Oregon. Judge Anna Brown agreed with Thrive and required the agency to provide monthly progress updates. Sens. Ron Wyden and Jeff Merkley, along with Reps. Earl Blumenauer and Greg Walden, also moved things along by passing the Mt. Hood Cooper Spur Land Exchange Clarification Act in 2018, with one section reading:

“In addition to or in lieu of monetary compensation, a lesser area of Federal land or non-Federal land may be conveyed if necessary to equalize appraised values of the exchange properties, without limitation, consistent with the requirements of this Act and subject to the approval of the Secretary and Mt. Hood Meadows.”

While the Omnibus Act laid out very specific terms — 770 acres at Cooper Spur for 120 acres in Government Camp — the Clarification Act provided more leeway “if necessary.” The section above, and that actionable language, is critical to remember as USFS got further into its formal decision process.

•••

Part II will focus on the last six years of the Government Camp-Cooper Spur land exchange, particularly why the deal collapsed and two pending court cases key to resolving it.